A ceramic bowl placed atop a paper tablecloth in a Saint-Malo crêperie, an orange-hued syrup so sweet that kids are allowed to sip it, supermarket shelves stocked with labels bearing Breton crosses and Celtic-style fonts… Clichés about cider abound in France, thanks in large part to the sector’s rampant industrialization. According to a report by the Union Nationale Interprofessionelle Cidricole, nearly 85% of the French cider market is controlled by just two agricultural cooperatives: the Eclor group, which produces nearly half of all major retail brands (including Loïc Raisin, Ecusson and Kerisac), and Les Celliers Associés, which owns Val de Rance, another brand that dominates soulless crêperies and supermarket aisles. “The cider industry is plagued by this image of a highly carbonated and extremely sweet drink. This type of cider is practically soda, even though you have to admit that it’s kept Brittany and Normandy’s apple orchards afloat,” explains Saumur-based producer Côme Isambert. “It’s thanks to these agricultural cooperatives that there are still fruit trees in France,” adds the Côtes-d’Armor cider maker Johanna Cécillon.

But when it comes to these two producers, you can say goodbye to the addition of yeasts and CO2! Down with added enzymes and sulfites! Ciao to caramel flavorings! Much like craft beer and natural wine producers, these cider makers praise the merits of heirloom varieties of their fruit, natural carbonation that occurs in the bottle, and pure, unpasteurized nectars. In other words: apples, apples, apples… and, occasionally, a few pears. Other such enthusiastic new-age producers include Cyril Zangs, Isabelle Richard or even Jacques Perritaz. In their orchards and cellars, these producers focus on the essence of the fruit itself, the juice extracted from it, the Ding an Sich of cider. They insist upon the diversity of their flavors, the respect for the microbial life of their products and the honesty of their process – prerequisites when it comes to fully savoring the uncorked bottle.

Apples and grapes never fall far from the stem!

Low in alcohol content, relatively refreshing, produced locally and inexpensive, cider pretty much encapsulates what many consumers are looking for these days – consumers, who, it should be mentioned, don’t really like hard alcohol – otherwise why would they add coke to their whiskey? Sniffing out a money-making opportunity, “disruptive” booze start-ups wanted to revitalize the drink’s image via some highly effective marketing campaigns. With new labels and catchy taglines celebrating the crispness, lightness and naturalness of a drink made entirely from freshly-picked orchard fruit, these fermentation entrepreneurs paved the way for the true cider revolution, even if they failed to make good cider in the process.

© Hugo Denis-Queinec

And the selection of craft ciders available on the market today is as exciting as the purge was long. Apple or pear, tranquille (known in English as “still” or non-sparkling) or extra dry, blended with other “naturopathic” alcohols, aged in Calvados casks, co-fermented with walnuts or raspberries, cryogenized or aged, the list goes on. “There’s an incredible amount of diversity when it comes to apples and pears – and a terroir that’s potentially even greater than that of wine,” argues Côme Isambert. A diversity that’ll have you smacking your lips together and which even feels a little punk rock at times, reminiscent of the early days of the natural wine movement. In fact, many of these cider producers lay claim to that very movement: “We treat our fruit varieties as if they were grape varietals, playing with different blends,” explains Johanna Cécillon from her estate located between Dinan and Saint-Brieuc. “I have a hard time describing myself as a cider maker: I make pear cider as if it were a pet’ nat’ wine, I try to find the purest expression of the pear through its deposits, tannins and acidity… and above all, I try to avoid sugar,” explains the naturalist Côme Isambert.

Apple of my eye

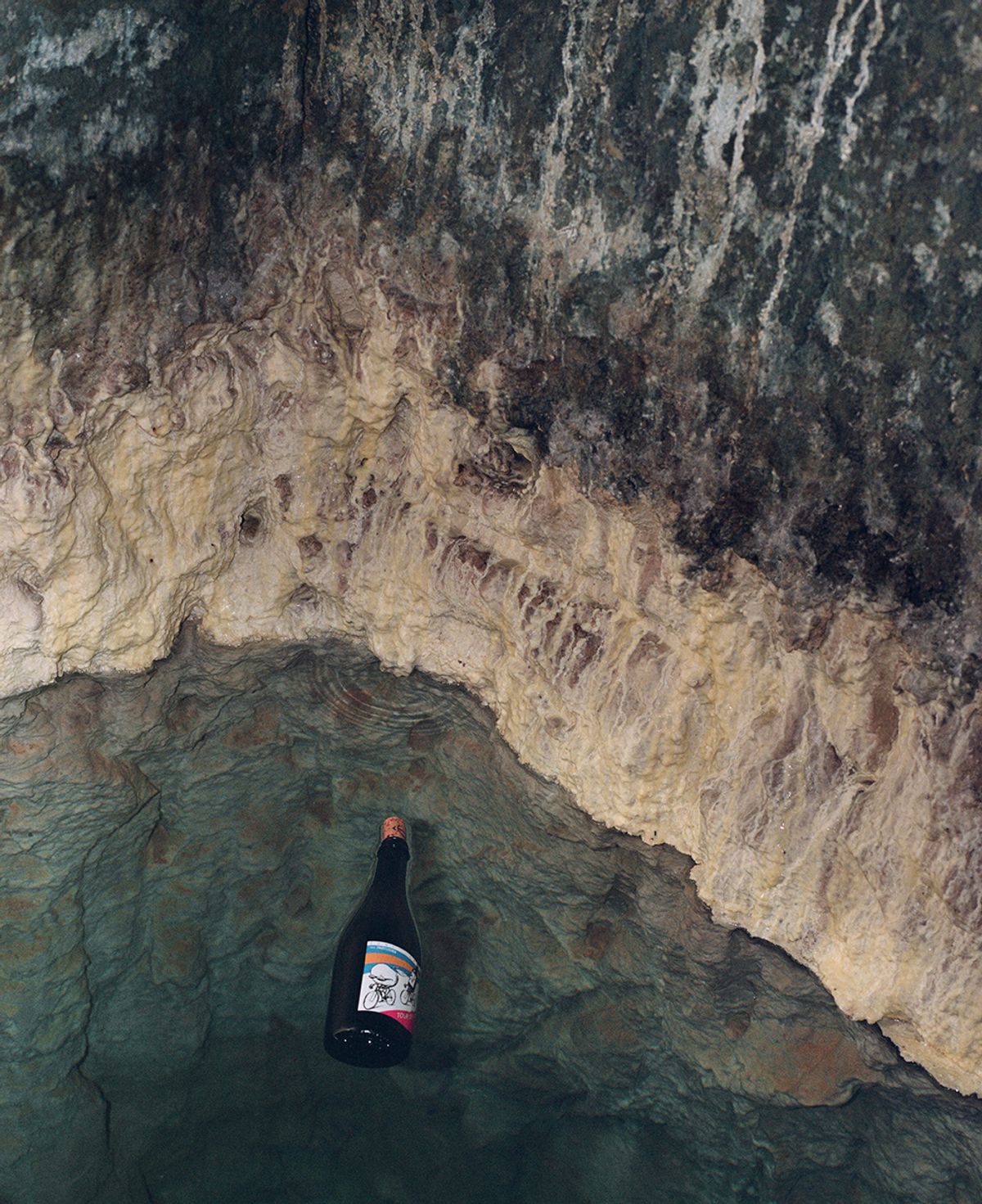

Environmentally-friendly as long as it’s done on a human scale, cider farms, with their apple trees and hedges, also allow farmers to diversify their revenue streams. They might produce cider alongside beekeeping or livestock operations, and thus find some economic balance that allows them to approach each new harvest more serenely than the majority of winemakers. Strengthened by their differences, this new generation of cider makers wholeheartedly rallies together behind a set of guiding principles, while also caring for their newfound notoriety. In the Cotentin Peninsula, nine cider producers founded the “Vieillissement Prolongé” project which aims to age their bottles of hard cider so that with time and patience, they might earn the luxury of new flavor profiles. Elsewhere, the crème de la crème of independent cider producers has joined forces in an association called Les Brigades du Cidre, made up of a band of rebels, notably Cyril Zangs, Marc Abel, Jacques Perritaz, Côme Isambert, Cédric Le Bloas, Antoine Marois, Marc Frocrain and Isabelle Richard.

Prepared as natural nectars, their bottles have made their way onto the tables of prestigious restaurants and into the country’s best wine shops. But consuming these ciders also means enjoying the diversity of France’s fruit-growing regions, building a personal cellar, and supporting a younger generation that cares about the quality of its products, the beauty of its landscapes and the health of the environment. So there’s no need to hesitate any longer: drink your apples!

© Hugo Denis-Queinec

Ready to roll up your sleeves and get your hands dirty? To kick off your exploration of the cider world, aim for simplicity. Fill your glass with a so-called “mono-varietal” fruit cider, aka one made from a single variety of apple or pear. This is the most intense expression of the orchard, soil turned fruit, allowing you to understand that each variety is unique, much like grapes. Try something like the Fossey pear cider, bottled by Jérôme Forget: simple, elegant, crisp and structured – quite simply one of the best nectars in France. Not fully convinced yet? Let yourself be tempted by a still cider, more specifically one of the explosively flavorful versions made in the Basque Country, like a bottle of Txalaparta produced by the Domaine Bordatto. Ready for some more complex and therefore more surprising fermentations? Pop open a walnut or raspberry cider, fragrant without being overwhelmingly so, obtained through co-fermentation or maceration. Get your hands on the incredible Lotto’fruits by Côme Isambert, an apple and pear cider from Normandy blended with grapes (Chenin, Grolleau gris) and strawberries – a lovely dry cider bursting with notes of red summer berries. Finally, hunt down some unidentified drinking objects in the very independent section of your local supermarket, like one of Cyril Zangs’ blends, who has teamed up with Ardèche winemaker Andréa Calek to make a “widre” (50% wine, 50% cider), or even the mind-blowing Mon Coeur Balance co-ferment, made with Guillevic apples and Gamay grapes, produced by La Cidrerie du Golf.

Victor Coutard is a journalist and author of books defending the good name (and flavor) of butter and pine bark.